AVK for GGG: A look inside a textbook French bistro

Paris, Dining, Etiquette

A Guide to Dining in Paris: Understanding Different Types of Restaurants

Bistro, Brasserie, Café: Where and How to Eat in Paris

Alexander

To eat in Paris is to participate in a centuries-old ritual, a choreography of unspoken tradition, and atmosphere.

Introduction to Parisian Dining

The city has elevated dining into an art form, where the distinctions between a café, a bistro, and a brasserie are not just semantic but spatial, cultural, and temporal. Knowing the difference is not about snobbery; it is about fluency, and being able to communicate with and interact with the experience you wish to have.

Ernest Hemingway once wrote that Paris is “a moveable feast,” and indeed it is—but only if you know where, when, and how to sit at the table. From zinc-topped café counters to wood-paneled bistros on side streets, each type of establishment has its own rhythm and rules. Some are designed for lingering, others for efficiency; some for locals, others for theatre; all of them, in their way, reveal something about Paris itself.

This guide is not a restaurant list.

It is a primer on how to read the Parisian dining landscape: how to understand what kind of place you’re walking into, what it expects of you & what you can probably expect from it, and how to enjoy it fully and gleefully—ideally with a glass of wine in hand.

The Parisian Restaurant Landscape: A Matter of Style & Timing

The Parisian dining world is not easily reducible to “casual” or “formal.” Rather, it’s an ecosystem shaped by history, habit, and a distinctive French regard for mealtime as a protected moment of pleasure.

Here’s a general orientation:

Café: Social hub, open all day, primarily for drinks, light food, and people-watching. Think espresso, tartine, apéro.

Bistro: Intimate, traditionally family-run, offering simple but soulful meals. Often dinner-focused.

Brasserie: Larger, livelier, and more theatrical. All-day dining with a full menu—often open late or even 24 hours. Some of the old-glory Parisian establishments, and their quiet-but-impressive contemporaries fall squarely into this category.

Restaurant: Formal, often reservation-only, with more structured service and prix fixe options.

Others: Crêperies, wine bars (bars à vin), and salons de thé round out the picture, each with their own tempo and specialties.

Café Culture: Coffee, Wine & the Art of Watching the World Go By

In Paris, the café is a cultural institution as much as a culinary one. It is the city’s drawing room, its street-side stage, and its democratic salon. The menu may be short, the coffee average, and the service indifferent—but none of that is the point. The café is not about gastronomy. It’s about presence.

And in this sense, it’s an interesting equivalent to the classic British Pub.

Cafés have existed in Paris since the late 17th century, when the first coffee houses were introduced by way of the Ottoman Empire – this itself is a story which dates to Vienna, via the Ottoman siege of 1683, where the Austrians were rescued by by King Jan Sobieski III of Poland, along with help from others.

By the 18th century, cafés were meeting places for writers, thinkers, and revolutionaries—Voltaire was said to drink up to 40 cups of coffee a day at Café Procope, the city’s oldest, though this is one of these delightful bits of entertaining-and-somewhat-dubious ephemera.

Professional private tour guides in Paris and elsewhere live for this sort of thing, and its dissemination to their travelling guests is part of what makes their services so enjoyable. We have the best, and we live to share them with you, but we digress here...

During the 19th century, cafés multiplied across the city, evolving into the everyday institutions we know today: not places of radical discourse, necessarily, but of ritual and observation.

The classic café rhythm is seasonal and social. In the morning: espresso and a tartine (a sliced baguette with butter and jam). At midday: a plat du jour if the café offers it, or something light like a croque monsieur or salad. In the afternoon: un café crème and something sweet, perhaps a tarte aux pommes. In the early evening: apéro hour, when the zinc bar fills with glasses of pastis, wine, or kir.

And always, at every hour, cigarettes curling skyward, conversations rising and falling like birdsong, and the traffic of the city flowing by. If this all sounds a bit floral, well, it is, and the only thing to be done is tell it as it is.

The best seats are outside—even in winter, with heaters overhead and coats buttoned to the chin. You are not there to stare at your phone.

You are there to look up. As the poet Paul Éluard said,

“There is another world, but it is in this one.”

The café is where you learn to see it.

There are no reservations. You find a table, wait for a nod from the server, and order politely. Service is not rushed. You may linger for hours over one drink, and no one will mind—as long as you behave as a Parisian would: attentive to the moment, content to watch the theatre of the street unfold.

Oh, and have a glass of champagne, will you?

Bistros: Home-Style Meals with Soul

If cafés are for lingering, bistros are for eating. Not hurriedly, but hungrily—and well. The Parisian bistro offers a certain kind of intimacy: fewer tables, blackboard menus, no-frills warmth, and food that tastes like someone’s mother cooked it... if that someone’s mother trained at Le Cordon Bleu but preferred butter (the three most important French ingredients of course being butter, butter, and also butter) to ceremony.

The word “bistro” is thought to have entered French from the Russian word bystro (quick), shouted by occupying Cossacks in 1814 who wanted to be served fast. The historical truth is murky, but the name stuck, and ironically, bistros are not particularly fast at all. What they are is unpretentious. Their roots lie in the working-class eateries of 19th-century Paris: small, family-run kitchens serving hearty fare to neighbours, labourers, and students.

You’ll know a bistro by its narrow doorway, handwritten ardoise menu, checkered napkins, and worn wooden chairs, often the very same bentwood Thonet-style café chairs that you will also see in Vienna.

The food is seasonal and direct: œufs mayonnaise, boeuf bourguignon, poulet rôti, gratin dauphinois, tarte Tatin. Wine comes by the carafe. The service is often brisk but rarely cold. This is all about function.

Bistros are often only open for lunch and dinner. Unlike cafés, which keep the doors swinging all day, bistros shut down between services. Many still operate on tradition: no reservations, or only by phone. You come when you can, and hope for a table. If you’re lucky, you’ll be squeezed between two locals, both debating whether the steak-frites is better this week than last. You should probably join them again next week so that you can participate.

This, by the way, is also the perfect place to order a ridiculously, life-changingly perfect medium-rare hamburger.

In recent years, the bistro has undergone a revival through what Parisians call bistronomie: chefs returning to humble spaces to cook ambitious food at neighborhood prices. The results can be spectacular, but the spirit remains the same: welcoming, generous, honest. A good bistro never tries to impress. It simply nourishes.

As George Orwell once wrote (albeit of a different kind of Paris): “A man who has nothing should not be treated as nothing.” The bistro, in its purest form, agrees.

Brasseries: Big, Bold, and Always Open

If the café is your living room and the bistro your kitchen, the brasserie is the dining hall—grand, theatrical, and reliably buzzing. These are the places with mirrored walls, globe lamps, white-aproned waiters, and menus that read like a love letter to French culinary tradition.

Walk into a proper brasserie and you enter into a scene, and in the older of these, probably a story about 19th century courtesans testing the authenticity of the gems gifted to them by their wealthy clients by scratching them against the mirror-glass.

The word brasserie originally meant “brewery.” In 19th-century Alsace, breweries began serving hearty food alongside their beer, and the concept migrated to Paris, especially after the Franco-Prussian War brought a wave of Alsatian refugees into the capital. These establishments evolved into all-day restaurants known for generous plates, fast service, and beer (yes), but also for seafood platters, grilled meats, and classic dishes that don’t change with trends.

Here we come to one of the more misguided critiques of French cuisine—that it’s all the same dishes everywhere.

The answer is of course ‘not quite’, and if you honestly believe this, let us encourage you to experiment with some of the younger and more creative brasseries, who will casually knock your socks off. This is the "modern European" style of cooking that you will find particularly well rendered elsewhere, in particular somewhat unlikely-sounding destinations, such as Kraków.

And at the same time, there is deep comfort in knowing that the classic French Brasserie dishes remain so unchanged because they are, in fact, perfect.

A traditional brasserie menu might include choucroute garnie, steak au poivre, sole meunière, huitres (oysters) on crushed ice, and a range of desserts from crème brûlée to baba au rhum. There’s a certain abundance here—portions tend to be larger, the wine list longer, the service brisk but polished. And unlike the tight-lipped bistro, a good brasserie always welcomes walk-ins.

Brasseries are also where you’ll find Paris’s time-bending dining hours. While many restaurants close between lunch and dinner, the brasserie remains open—sometimes until midnight, sometimes longer. It’s where the theatre crowd dines after curtain, and where lunch meetings stretch well into the afternoon.

Some of the most famous brasseries—like La Coupole, Bofinger, or Brasserie Lipp—were once haunts of Hemingway, Sartre, Colette, and even Trotsky. Today they may be a touch more polished and tourist-heavy, but they haven’t lost their role as markers of urban elegance and endurance.

To dine at a brasserie is to inhabit a certain Paris: not the one of candlelit romance or bohemian rebellion, but of self-assured tradition.

As the old Parisian saying goes, “Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose.” The more things change, the more they stay the same—and at a brasserie, that’s exactly the point.

Formal Restaurants: The Art of Dining

In Paris, the formal restaurant is less about opulence and more about orchestration. These are places where the tablecloths are crisp, the pacing deliberate, and the service conducted with the poise of a chamber orchestra. You are participating in a ritual refined over centuries.

The tradition of formal French dining owes much to the grande cuisine of the 17th and 18th centuries, codified by chefs like La Varenne and Carême, and later systematised by Auguste Escoffier in his 1903 book Le Guide Culinaire, written while the master was still working at the Carlton Hotel in London.

It was Escoffier who introduced the brigade de cuisine—the kitchen hierarchy still used in fine restaurants today—and helped create the multi-course structure and à la carte service we now associate with haute cuisine. While Michelin stars didn’t arrive until the 20th century, quite frankly because they needed automobiles and Michelin tires to be worn out driving to fun places to eat, the reverence for culinary precision and layered complexity was already deeply embedded.

In a formal Parisian restaurant, the meal unfolds like theatre. There may be amuse-bouches (mouth-amusement) before you’ve even ordered, a sommelier to guide your pairing, and occasionally even silver cloches lifted in quiet synchrony. The menu dégustation (tasting menu) is common, and often the best way to experience a chef’s vision. Even a relatively modest establishment may offer a carefully curated menu fixe—three or four courses, perfectly balanced, and rooted in seasonality.

Reservations are often essential, especially for dinner. In some cases, booking weeks in advance is expected—particularly for restaurants with a Michelin star (or several). Many of these places have fixed seatings, and walk-ins are rare. The dress code is typically understated elegance, and often fully unstated: think tailored, not flashy. A jacket is always safe; jeans and sneakers are not – but you knew that already anyways.

But while the surroundings may be hushed and the service practiced, the experience is not meant to intimidate, but to be thoroughly and completely enjoyed. At its best, the formal Parisian restaurant is an act of generosity—an offering of artistry and care. It asks only that you show up prepared and excited to pay attention and explore what it is offering you.

As Julia Child, who trained in Paris, once wrote:

“In France, cooking is a serious art form and a national sport.”

The formal restaurant is where that seriousness comes to the table—not with stiffness, but with joy writ large.

Other Notables: Wine Bars, Crêperies & Salons de Thé

Paris is a city of invention, reinvention, and niche traditions that quietly flourish in the margins of its own semi-compulsive obsessions. If you wander off the main boulevards and into the side streets, you’ll find smaller spaces that reflect both deep-rooted culinary customs and newer Parisian habits.

Bars à Vin: Where Wine Comes First

In recent years, bars à vin—wine bars—have emerged as essential fixtures in many Parisian neighbourhoods. These are places where wine is the main event, and food, while often excellent, plays a supporting role. Look for hand-written chalkboards listing natural wines, biodynamic vintages, or obscure appellations from Corsica or the Jura. Small plates—charcuterie, fromage, seasonal vegetables, terrines—are the thing to look out for here.

Some are polished, others wildly casual. But most share a quiet mission: to help you drink better, with fewer rules and more joy. They are popular with Parisians, and with those travellers who prefer to lean into the aperitif hour, rather than rush toward a heavy meal.

Crêperies: Breton Soul in a Paris Wrapper

Though originally from Brittany, crêperies have long since taken root in Paris, especially around Montparnasse. The classic savoury galette—made with buckwheat flour—is filled with combinations like egg, ham, and cheese (complète), or mushrooms and crème fraîche. Sweet crêpes follow, topped with lemon and sugar, salted butter caramel, or Nutella (though the latter is less traditional).

Crêperies are often compact, unfussy, and excellent for a casual lunch or light dinner. Some serve Breton cider in traditional ceramic cups, a pairing that captures something rustic and unmistakably French.

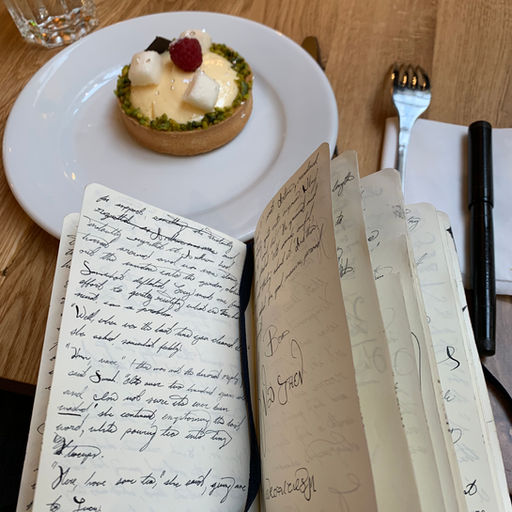

Salons de Thé: A Quiet Pause

While cafés may dominate the public imagination, salons de thé offer a quieter kind of refinement. These tea salons tend to be elegant and feminine in atmosphere, serving delicate pastries alongside a serious tea menu. Expect a hushed interior, white porcelain, and perhaps a small sandwich or quiche du jour. Ladurée is the most famous name, and Mariage Frères the venerable-and-iconic institution, but many independent tea salons offer a gentler charm—and fewer queues.

They are often overlooked by visitors, but for solo travellers, readers, or those in need of an afternoon’s peace, they’re a gift.

Etiquette Tips & Things to Know

Dining in Paris runs on its own quiet codes—understand them, and you’ll feel the difference immediately, and find that you can fluently move from one place to the next with ease. The goal is not to perform Frenchness, but to move through the experience knowing that these are not rules, not exactly. They’re more like cues to the choreography.

1. Reservations: When They Matter

Many restaurants, especially bistros and formal dining rooms, expect reservations—even for lunch. Walk-ins may be welcomed, but often only early or late. A phone call the day before is still considered good form, even if the website says they’re on Instagram.

2. Don’t Expect the Bill

The bill (l’addition) will not arrive unless you ask for it. This is not neglect—it’s courtesy. A Parisian meal is not meant to be rushed. When you’re ready, make gentle eye contact, and a very understated and subtle version of the universal ‘bill please’, or ask, “L’addition, s’il vous plaît?”

3. Tipping: It’s Optional, Not Obligatory

Service is included (service compris) in the bill by law. Still, it’s common to leave a small token—a euro or two for coffee, 5–10% at a restaurant—if the service was warm. If you are with friends in a proper gourmet temple which has provided you with grand artistry and service, and a commensurately grand bill reflecting this, certainly you can consider something like 50 euro, for example. Cash is appreciated, though not expected.

4. Bread Goes on the Table

You may not be given a bread plate. It’s perfectly acceptable—and normal—to rest your slice of baguette directly on the tablecloth, to the left of your plate. This confuses many foreigners, but the French table is more tactile than fussy.

5. Quiet Confidence Wins

Speak softly. Gesture less. Don’t call for a waiter by snapping or waving. A polite “Monsieur?” or “Madame?” goes a long way. The service may feel slower than elsewhere in the world, particularly North America, but that’s by design. Meals are meant to unfold, not be devoured.

6. Language: Politeness first. Try, Then Relax

A simple bonjour when entering and merci, au revoir when leaving makes all the difference. This is one of these small French details which often seems to get lost—remember that the French value simple courtesy, acknowledgement, and politeness substantially more than you may be used to. You don’t need perfect French. Just the effort, and polite acknowledgement. And if your server switches to English, take it as kindness, not condescension.

Final Thoughts: It's About Culture, Not Just Great Food

Paris is about making a conscious decision that meals are not interruptions in the day, but the rhythm that holds it together.

Understanding the difference between a café and a brasserie isn’t about mastering a system. It’s about tuning in to the city’s quieter messages—its tempos, its manners, its joy in small rituals done well.

When you sit down in the right kind of place, at the right time of day, and order just the thing you’re in the mood for, you’ll know you’ve understood more than the menu.

And Paris, in turn, will reward you.